Mycelium Network Society, 2018, Opening Night Performance

Post-Nature-A Museum as an Ecosystem

Taipei Biennial 2018

Taipei Fine Arts Museum

November 11, 2018-March 10, 2019

The term post-nature carries a certain initial shock. And well it should. It’s a wake up call to change how we as human beings think about ‘nature’ – and transition toward ecological republicanism[i]: to consider ourselves embedded in the natural world, symbiotically dependent upon Earth systems, flora and fauna, and to become members in the Parliament of Things.[ii]

Post-Nature-A Museum as an Ecosystem, at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), presented this pluralist stance. Visitors engaged with a broad spectrum of creative approaches to environmental issues and ideas, encompassing numerous cultures and nationalities. While the exhibition sought to inform and teach, I found it poetic and enveloping, not pedantic. The museum was “the central nervous system”[iii] of the biennial, modeling a less top-down hierarchy than the norm (instead of arbitrating aesthetic exceptionalism) – acting as a porous interchange among many agents, becoming post-natural – to leave behind worn out assumptions about ‘nature,’ and the idea that human beings are somehow exempt or immune from the symbiotic commons of survival.

Taipei Fine Art Museum

Co-curators Mali Wu and Francesco Manacorda brought together artists, scientists, sociologists, urban planners, activists, theorists and NGOs whose focus ranged from maintaining bushwalking trails, to organising against the endangerment of Taiwan’s Indigenous lands and culture – from listening to the songs of sea creatures, to petitioning the government of Scotland to view the inevitable effects of global warming as an opportunity for generating income.

In lieu of the usual theory-heavy biennial format, Wu and Manacorda curated an exhibition that was challenging and provocative, yet accessible – championing museums and institutional practice as “ever-changing and osmotic.”[iv] There was little pretension, and this appeared to have paid off in public attendance: according to Wu, as of 28 February (with one week left to go), more than 170,000 people had attended. Evidently, she was correct in her perception that, “the time is right for Taiwan to face its environmental challenges.”[v]

KE Chin-Yuan, The Age of Awakening, 2018, documentary, 108 min © the Participant and TFAM

Water Buffalo bathing in pollution run-off, 1993

Of the forty-two artists/groups included in the exhibition, nineteen were Taiwanese. Historically a contested, colonised crossroads, Taiwan was plundered from the late 17th century onward by a string of empires, including the Chinese, Japanese, Dutch and Spanish, for its plentiful deer population, arable land, conscripted indigenous labour and abundant ports and coves. Following centuries of rule by a complex series of Chinese governments – and a political face-off between Communism and Democracy – martial law ended in 1987, and the country’s first democratic presidential election occurred in 1996. Today, relations with mainland Communist China are tense and have international implications, however, Taiwan is now a liberal democracy.

But during the second half of the twentieth century, Taiwan entered a state-mandated period of rapid industrialisation. The country’s minimal environmental regulations offered US and Japanese businesses unfettered, offshore production of electronics and other goods. Growth was exponential, and amounted to, “The Taiwan Miracle.” The country came to exemplify the “proliferation of flows of commodities, energy, money, desires, control and planning” characterising “the universal regulation necessary for advanced industrialization.”[vi] Great for the economic development of a small island nation: very bad for its natural environment.

KE Chin-Yuan, The Age of Awakening (Our Island), 2018, documentary, 108 min © the Participant and TFAM

Post-Nature’s curatorial vision was allied with feminist cultural theorist Donna Haraway’s concept of situated knowledges:

Situated knowledges are about communities, not about isolated individuals. The only way to find a larger vision is to be somewhere in particular.[vii]

Wu and Manacorda trusted to the local for greatest impact – by tapping into a broad array of Taiwanese artists and environmental groups. For example, ‘Open Green’ is a citywide, community-driven initiative to restore abandoned, closed or disused spaces, also rehabilitating and maintaining old waterways and trees. For the exhibition, the group presented a retrospective of its past projects and conducted public tours of various project sites as part of Ecolab – the Biennial’s installation on two floors hosting documentation of activities, outcomes of workshops, lectures and discussions. Since 2006, the ‘Taiwan Thousand Miles Trail Association’ has created community around discovering and building nature trails in local areas, to gain more understanding of local landscapes and connect with narratives of trails and people. Having generated an unbroken track reaching almost 3,000 km throughout Taiwan, this group has impacted the lives of many volunteers and hikers. The artist Ting-Tong Chang’s Pure and Remote View of Streams and Mountains, 2018 was painted with ink blackened by particulate matter extracted from Taipei’s air. Emblematic of asthma, cancer and other destructive effects of the city’s compromised air quality, this work enlisted an art therapist to collaborate with local asthma sufferers to create their own paintings using Chang’s ink (with their work eventually replacing his paintings over the course of the exhibition). The curators abstained from universalising these close-to-home efforts, embracing a ‘boots on the ground’ documentarian clout.

Ting-Tong Chang, Pure and Remote View of Streams and Mountains, 2018, mixed media, dimensions variable, film: approx. 7min © the Participant and TFAM

Ting-Tong Chang, Pure and Remote View of Streams and Mountains, 2018, detail showing asthma sufferers paintings on 10 March 2019; mixed media, dimensions variable, film: approx. 7min © the Participant and TFAM

One Thousand Miles Trail Association in Ecolab © the Participants and TFAM

One Thousand Miles Trail Association in Ecolab © the Participants and TFAM

The science historian and cultural theorist Bruno Latour, in his 2016 keynote lecture, On Sensitivity Arts, Science and Politics in the New Climatic Regime, argued for employing the arts to freely imagine response to environmental change as the climate warms, species disappear, and turning points call for innovation and,

“… sensitivity for the contradictions, complexities, novelties and size of the entanglement of humans and nonhumans”… “[to] become sensitive to something which is new, unusual and difficult to actually capture.” [viii]

Both Haraway and Latour are pioneering proponents of collaboration with self-organising powers of nonhuman processes for re-setting human behaviour within the natural world. Their ideas have influenced countless artists, including most in Taipei Biennial 2018.

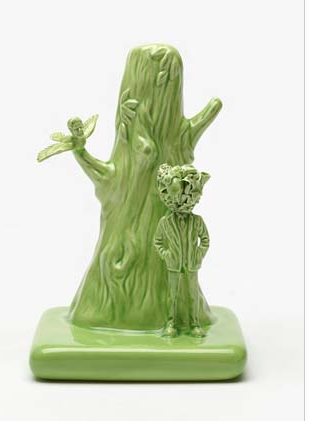

Mycelium Network Society (Franz Xaver+Taro +Martin Howse+Shu Lea Cheang+global

network nodes), Mycelium Network Society, 2018, mixed media, installation, 1000×800×360 cm © the Participants and TFAM

For example, Mycelium Network Society (MNS) “investigates the unique abilities of mycelium, the… thread-like networks of fungal cells, to share and process information.”[ix] MNS is a consortium of alternative art spaces and bio hack labs with nodes in France, the UK and USA and, now, Taiwan. Their large scale sculptural installation, Mycelium Network Society, 2018, for TB11, was a transparent acrylic atomic structure, with each sphere housing Ganoderma lucidum mushrooms and mycelium wired to transmit radio frequencies tracking changes in the mycelium.

Mycelium Network Society, detail

These radio transmissions were simultaneously emitted as a sound component into the exhibition space. For the Biennial opening, seventeen local sound artists performed on site, in response to Ganoderma’s radio frequency transmissions. Here, fungi and humans formed a call and response, rhythmic language, affirming human/nonhuman creative and entangled imaginaries.

Mycelium Network Society, TB11 Opening Night Performance

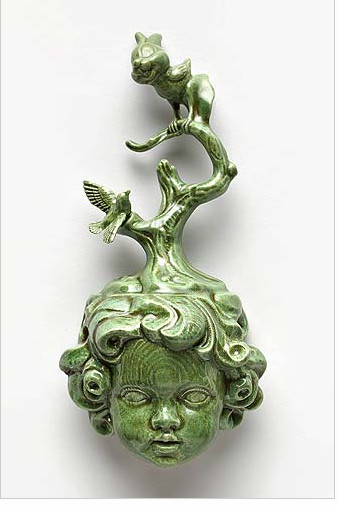

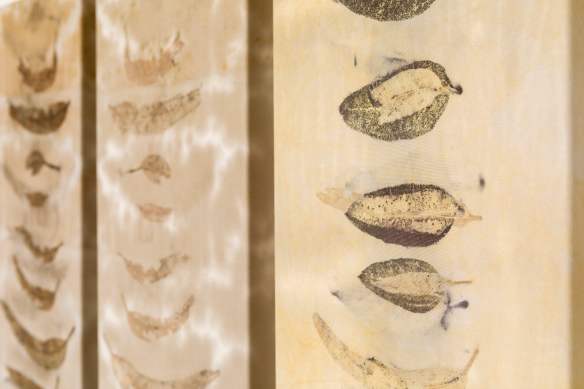

Helen Mayer Harrison & Newton Harrison, Making Earth, 2018, leaves, sand, clay, sewage sludge, and animal manure, 150x80x120 cm © the Participants and TFAM

Helen and Newton Harrison’s On the Deep Wealth of this Nation, Scotland, 2018 and Making Earth, 2018 confirmed how they have pioneered – since the 1960s – the visual culture of environmentalism in their mixed-media installations combining cartography, plants, sculpture and text. Making Earth, 2018 was a site-specific installation originally exhibited in 1970 California. An active compost pile contained inside a wooden crate, the piece was comprised of leaves, sand, clay, sewage sludge, and animal manure, turned and watered repeatedly to build a rich, biodiverse soil. This direct, performative action spoke of topsoil’s primacy to survival, while declaring itself both art and a member of the parliament of things through its non-art components and presentation outside the museum windows.

Helen Mayer Harrison & Newton Harrison, On the Deep Wealth of this Nation, Scotland, 2018, vinyl and print, 221×213×280 cm © the Participants and TFAM

On the Deep Wealth of this Nation, Scotland, was an open verse, illustrated prose poem outlining the artists’ remediation plan (which was presented to the Scottish parliament) for the country to be the first “to give back more to the Lifeweb than it consumes.” Deep Wealth valued all players in Scottish ecosystems, including trees, animals, human foragers, plants, fungi, and water, and merged with nonhuman temporalities. The Harrisons’ plan suggested that as a small post-industrial country with a carbon footprint three times its size, Scotland could alter the dynamic by taking advantage of its yearly water surplus and sequester, sell, trade and/or redirect the water to its drought-stricken farms. This pragmatic, long-term approach was also used to describe large-scale reforestation to sequester carbon dioxide, augment atmospheric oxygen, and generate income from sustainable wood harvests.

Helen Mayer Harrison & Newton Harrison, On the Deep Wealth of this Nation, Scotland, 2018, detail, vinyl and print, 221×213–280 cm © the Participants and TFAM

And yet, with all their common sense, the couple envisioned working seamlessly with the nonhuman world as equals, and wrote:

When carefully performed/This harvest preserves and even adds to/The diversity in this gifted forest/In a fantastic moment/I asked what our tree elder would say/ To being harvested/And the response came/When my usefulness to the whole diminishes/A change of state is acceptable

Ursula Biemann, Acoustic Ocean, 2018, video installation, color, sound, 18min©the Participant and TFAM

Swiss artist Ursula Biemann’s video essay Acoustic Ocean, 2018 was science fiction poetry, depicting a futuristic aquanaut on the rocky coast of northern Norway. We viewers watched as Sofia Jannok (an indigenous Sami singer and environmental activist) prepared remote sensing instruments to connect with other-than-human, underwater communities. Hearing their many voices, we were linked to whales, sea urchins, harbor seals, dolphins, spotted sea trout and other marine beings.

Ursula Biemann, Acoustic Ocean, 2018, video installation, color, sound, 18min©the Participant and TFAM

We stood together as transported witnesses in the darkened video projection room, while sounds and sights passed through us (and a whale passed by below the water’s surface). We listened to the aquanaut recount her grandmother’s story of climate warming’s destructive effects on reindeer who traditionally support Sami life. Here was the anthropological concept of multinaturalism, which implies a “frontier between cosmologies [of] animism and modern naturalism” –

… where nature ceases to be a stable unity in order to unfold as perpetual variation. On the one hand, we have an absolutist, naturalist ontology [Western empiricism]…. On the other hand, there lies an animist… ontology, fertile in blind spots, where difference is unsurpassable but always generative, and equivocations between perspectives foundational in negotiating a multinatural world. [x]

The aquanaut’s indigenous presence formed a bridge from the modern, rigid notion of controlled and subdued Nature, to an animist Nature that is malleable, changing and incorporative of many beings’ perspectives – with not all human beings’ worldviews leading to environmental destruction.

Indigenous Justice Classroom, Ketagalan Boulevard Arena, 2018, detail, installations, documents, videos, lectures, dimensions variable © the Participants and TFAM

For Taipei Biennale 11, Museum of Nonhumanity ( Gustafsson & Haapoja)

invited Taiwanese practitioners to reflect on the notion of animality from the perspective of their cultural knowledge and expertise. These contributions expand the conversation to East Asian perspectives on environmental protection, animal studies and indigenous rights. Video, 59:50 ©the Participant and TFAM

Taipei Biennial 11 invited us, as citizens of nature, to join with flora, fauna and other agents necessary to Earth’s systems, such as water, soil and minerals. As Istanda Husungan Nabu (Cultural Worker of Laipunuk) explained in, Taipei Biennial 2018/Museum of Nonhumanity:

I know that our Bunan tribe, in terms of the process of seeking life, is different than that in the Western world. Among the Paiwan, Pangcah and Alayal [other Taiwanese Indigenous groups], the fact is that these groups are very diverse…and allow differences among each other. [Today,] due to the concept of duality, humans and animals are divided into the managers and the managed.[xi]

I’ve chosen here to talk in some depth about just one thematic thread that was running through TB11 – that of reassessing the Western concept of a nature/culture split — when the Biennial held countless possibilities for in-depth focus and so many participants. I wanted to clarify how Post-Nature-A Museum as an Ecosystem connected the public to new ideas and feelings that could subsequently take root in the world outside the museum. Despite the huge environmental challenges currently facing humanity, art’s imaginative flexibility can build bridges to creative, hopeful futures. Embracing our role within the ecosystem known as ‘the Earth’ is a huge step toward that goal.

Gustafsson and Haapoja, Museum of Nonhumanity, 2016–ongoing, detail, video installation. © the Participants and TFAM

https://www.taipeibiennial.org/2018/

[i] Patrick Curry, “Redefining Community: Towards an Ecological Republicanism,” Biodiversity and Conservation 9:8 (2000) 1059-1071. “In so far as the common good of any human community is utterly dependent… upon ecosystemic integrity (both biotic and abiotic), that integrity must surely assume pride of place in its definition… and [be] maintained by practices and duties of active ‘citizenship’, whose larger goal is the health not only of the human public sphere but of the natural world which encloses, sustains and constitutes it.”

[ii] Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 145. In brief, Latour’s concept of the Parliament of Things gives every object on Earth (be it Monsanto, plants, soil, insects) an equal voice instead of separating mankind out as “more equal.”

[iii] Exhibition Guidebook, Introduction (Taipei: Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2018), 12.

[iv] Exhibition Guidebook, 14.

[v] Conversation with Mali Wu, 9 March 2019.

[vi] James Beninger, The Control Revolution: Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Society (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986), vi, as discussed in Erich Hörl, General Ecology: The New Ecological Paradigm (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 9.

[vii] Donna Harraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,’ Feminist Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn, 1988), 92.

[viii] Bruno Latour keynote for the opening of Performance Studies International at University of Melbourne, 5 July 2016. http://www.bruno-latour.fr/node/692 (Accessed 29 March 2019).

[ix] Exhibition Guidebook, 20.

[x] Pedro Neves Marquez, “How Many Natures can Nature Nurture? The Human, Multinaturalism, and Variation,” SKY (Elements for a World), (Beirut: Sursock Museum, 2016), 24. Here, Marquez is referring to the work of Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro.

[xi] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cXh943t98CE&ddlLang=en-us (accessed 18 March 2019).

Dark Matter – Shannon Berry-Bam (2017), Acrylic on canvas, 102x153cm. All photos courtesy the artist.

Dark Matter – Shannon Berry-Bam (2017), Acrylic on canvas, 102x153cm. All photos courtesy the artist. Master of Circus – Rudi Mineur (2016), Acrylic on canvas, 97x97cm.

Master of Circus – Rudi Mineur (2016), Acrylic on canvas, 97x97cm.

Sharon Berry-Bam and the Rosette Nebula (2016), Acrylic on canvas, 87x87cm.

Sharon Berry-Bam and the Rosette Nebula (2016), Acrylic on canvas, 87x87cm. Creative Fire – Asher Bowen-Saunders (2018), Acrylic on canvas, 97x97cm.

Creative Fire – Asher Bowen-Saunders (2018), Acrylic on canvas, 97x97cm. Broken Sleep – Richard Causer (2017), Acrylic on canvas, 138x102cm.

Broken Sleep – Richard Causer (2017), Acrylic on canvas, 138x102cm. Dream and Trust in Yourself – Sabine van Rensberg (2016), Acrylic on canvas, 96x96cm.

Dream and Trust in Yourself – Sabine van Rensberg (2016), Acrylic on canvas, 96x96cm.